-1-2.png)

Without a structured testing program, our experience shows that it’s very likely that most SEO efforts are at best taking two steps forward and one step back by routinely deploying changes that make things worse.

This is true even when the thinking behind a change is solid, is based on correct data, and is part of a well-thought-out strategy. The problem is not that all the changes are bad in theory - it’s that many changes come with inevitable trade-offs, and without testing, it’s impossible to tell whether multiple small downsides outweigh a single large upside or vice versa.

For example: who among us has carried out keyword research into the different ways people search for key content across a site section, determined that there is a form of words that has a better combination of volume vs competitiveness and made a recommendation to update keyword targeting across that site section?

Everyone. Every single SEO has done this. And there’s a good chance you’ve made things worse at least some of the time.

You see, we know that we are modelling the real world when we do this kind of research, and we know we have leaky abstractions in there. When we know that 20-25% of all the queries that Google sees are brand new and never-before-seen, we know that keyword research is never going to capture the whole picture. When we know that the long tail of rarely-searched-for variants adds up to more than the highly-competitive head keywords, we know that no data source is going to represent the whole truth.

So even if we execute the change perfectly we know that we are trading off performance across a certain set of keywords for better performance on a different set - but we don’t know which tail is longer, nor can we model competitiveness perfectly, and nor can we capture all the ways people might search tomorrow.

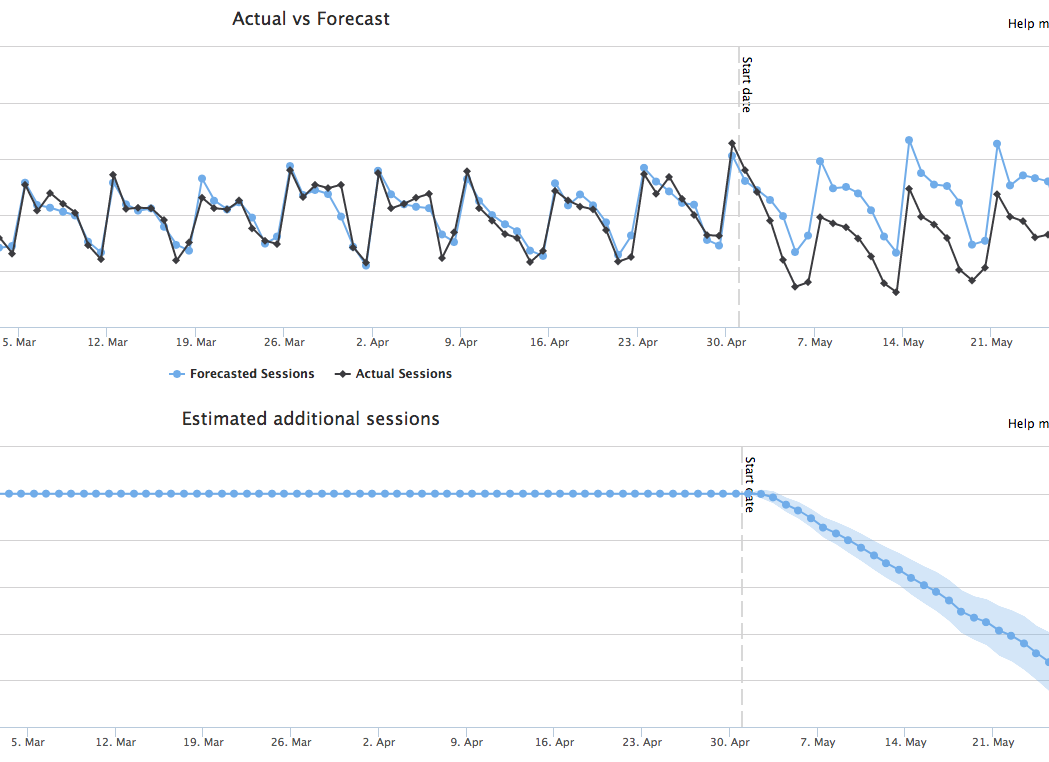

Without testing, we put it out there and hope. We imagine that we will see if it was a bad idea - because we’ll see the drop and roll it back. While that may be true if we manage a -27% variant (yes, we’ve seen this in the wild with a seemingly-sensible change), there is a lot going on with large sites and even a large drop in performance in a sub-section can be missed until months after the fact, at which point it’s hard to reverse engineer what the change was. The drop has already cost real money, the downside might be obscured by seasonality, and just figuring it all out can take large amounts of valuable analysis time. When the drop is 5%, are you still sure you’re going to catch it?

And what if the change isn’t perfect?

The more black-box-like the Google algorithm becomes, the more we have no choice but to see how our ideas perform in the real world when tested against the actual competition. It’s quite possible that our “updated keyword targeting” version loses existing rankings but fails to gain the desired new ones.

Not only that, but rankings are only a part of the question (see: why you can’t judge SEO tests using only ranking data). A large part of PPC management involves testing advert variations to find versions with better clickthrough rates (CTR). What makes you think you can just rattle off a set of updated meta information that correctly weights ranking against CTR?

Our testing bets that you can’t. My colleague, Dominic Woodman discussed our successes and failures at Inbound 2018, and highlighted just how easy it can be to dodge a bullet, if you’re testing SEO changes - see: What I learned From Split Testing

We’re talking about small drops here though, right?

Well firstly, no. We have seen updated meta information that looked sensible and was based on real-world keyword data result in a -30% organic traffic drop.

But anyway, small drops can be even more dangerous. As I argued above, big drops are quite likely to be spotted and rolled back. But what about the little ones? If you miss those, are they really that damaging?

Our experience is that a lot of technical and on-page SEO work is all about marginal gains. Of course on large sites with major issues, you can see positive step-changes, but the reality of much of the work is that we are stringing together many small improvements to get significant year-over-year growth via the wonders of compounding.

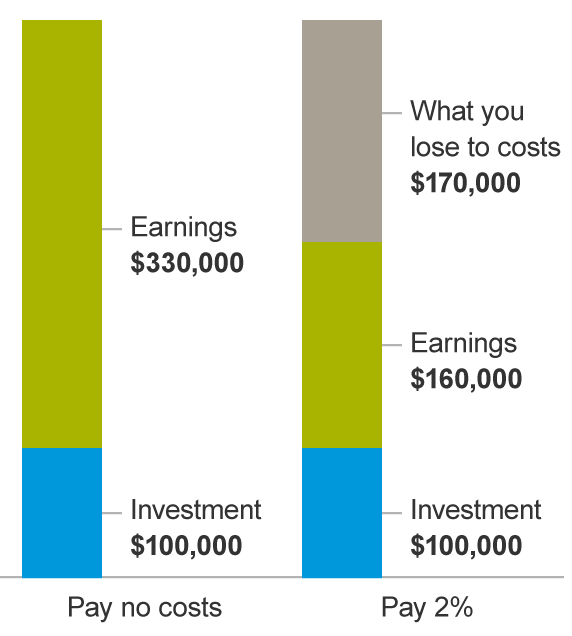

And in just the same way that friction in financial compounding craters the expected gains (from this article of the effect of fees on investment returns):

If you’re rolling out a combination of small wins and small losses and not testing to understand which are which to roll back the losers, you are going to take a big hit on the compounded benefit, and may even find your traffic flatlining or even declining year over year.

You can’t eyeball this stuff - we are finding that it’s hard enough to tell apart small uplifts and small drops in the mix of noisy, seasonal data surrounded by competitors who are also changing things measured against a moving target of Google algorithm changes. So you need to be testing.

No but it won’t happen to me

Well firstly, I think it will. In classroom experiments, we have found that even experienced SEOs can be no better than a coin flip in telling which of two variants will rank better for a specific keyword. Add in the unknown query space, the hard-to-predict human factor of CTR, and I’m going to bet you are getting this wrong.

Still don’t believe me? Here are some sensible-sounding changes we have rolled out and discovered resulted in significant organic traffic drops:

- Updating on-page targeting to focus on higher-searched-for variants (the example above)

- Using higher-CTR copy from AdWords in meta information for organic results

- Removed boilerplate copy from large numbers of pages

- Added boilerplate copy to large numbers of pages

Want to start finding your own marginal gains? Get in touch to find out more about SearchPilot and how we are helping our customers find their own winners and losers.