This post is based on a presentation I gave at BrightonSEO in October 2022 - you can check out the slides and a recording here.

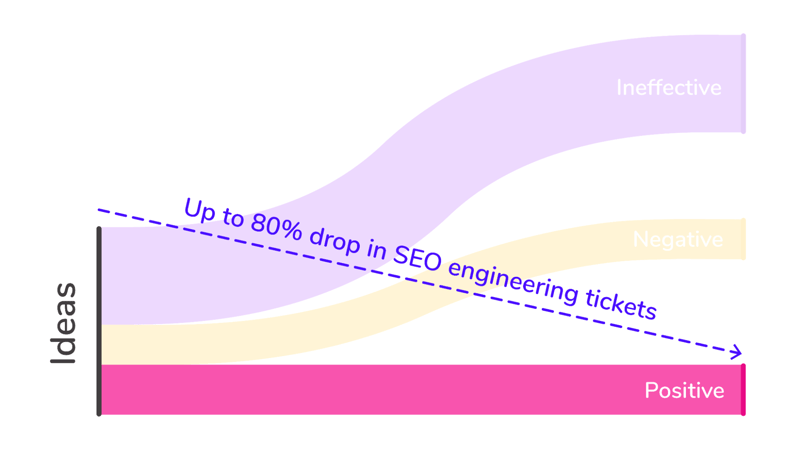

What do you think your engineering team’s reaction would be if you told them that you had a plan to get all of the benefit of the on-site SEO work you wanted to do in the coming year, but you were only going to create 20% of the engineering tickets you normally would?

While the best engineering teams love doing commercially-valuable work, very few enjoy the iterative process of tweaking and re-tweaking that optimisation involves almost by its nature. We’ve all experienced the disappointed conversations where it becomes clear that SEO wants engineering to implement yet another form of structured data, make changes to metadata based on keyword research, or modify which sibling pages appear in “related products” widgets yet again. They’ll do the work, of course, because organic search is responsible for the lion’s share of traffic to the website and an even greater disproportionate amount of the new revenue. But they would be thrilled to learn that there is a way of capturing all that benefit with less of their time. At SearchPilot, we even enable teams to immediately capture positive impacts with our meta-CMS functionality while the engineering team do the hard work of developing the code.

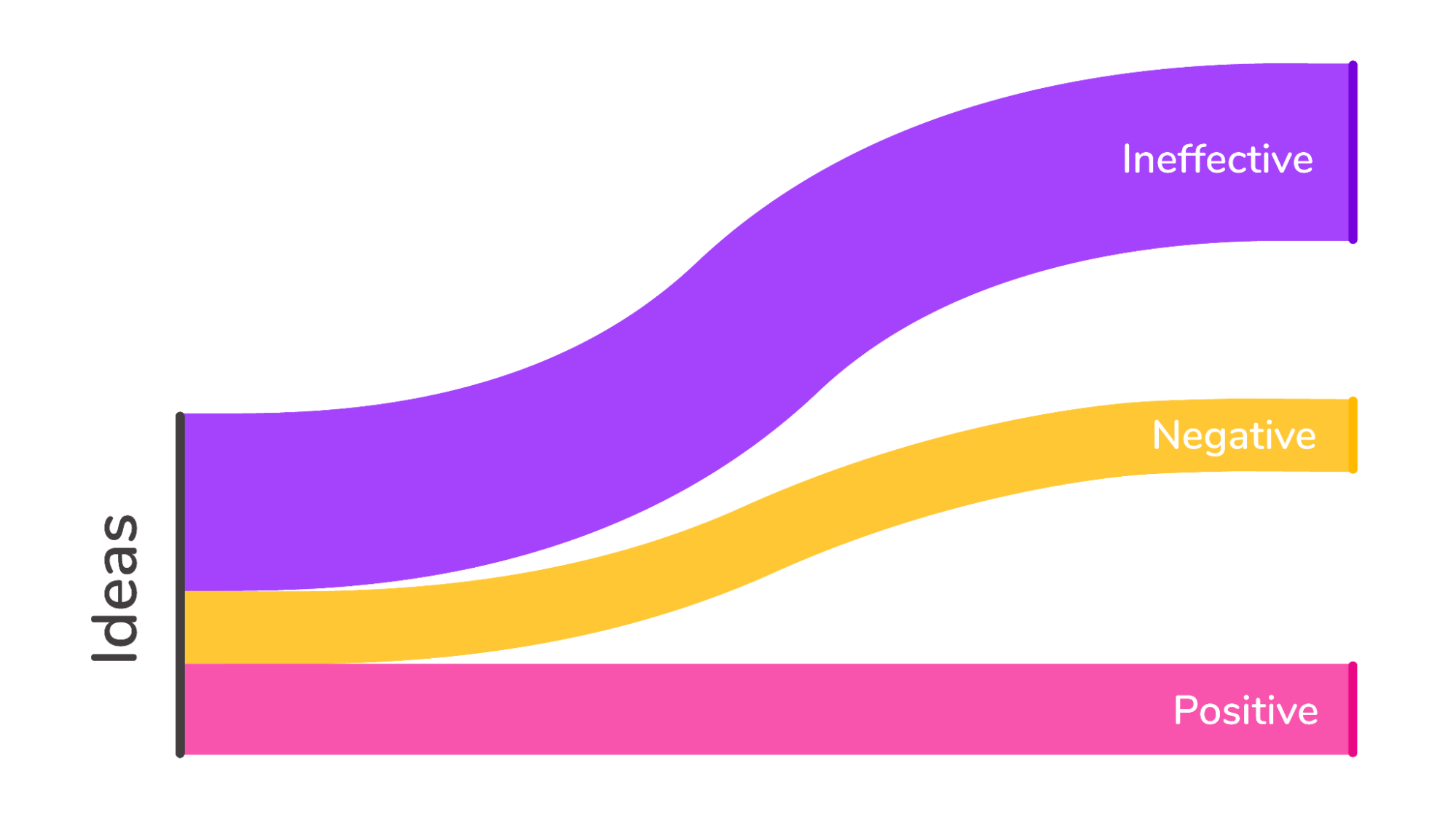

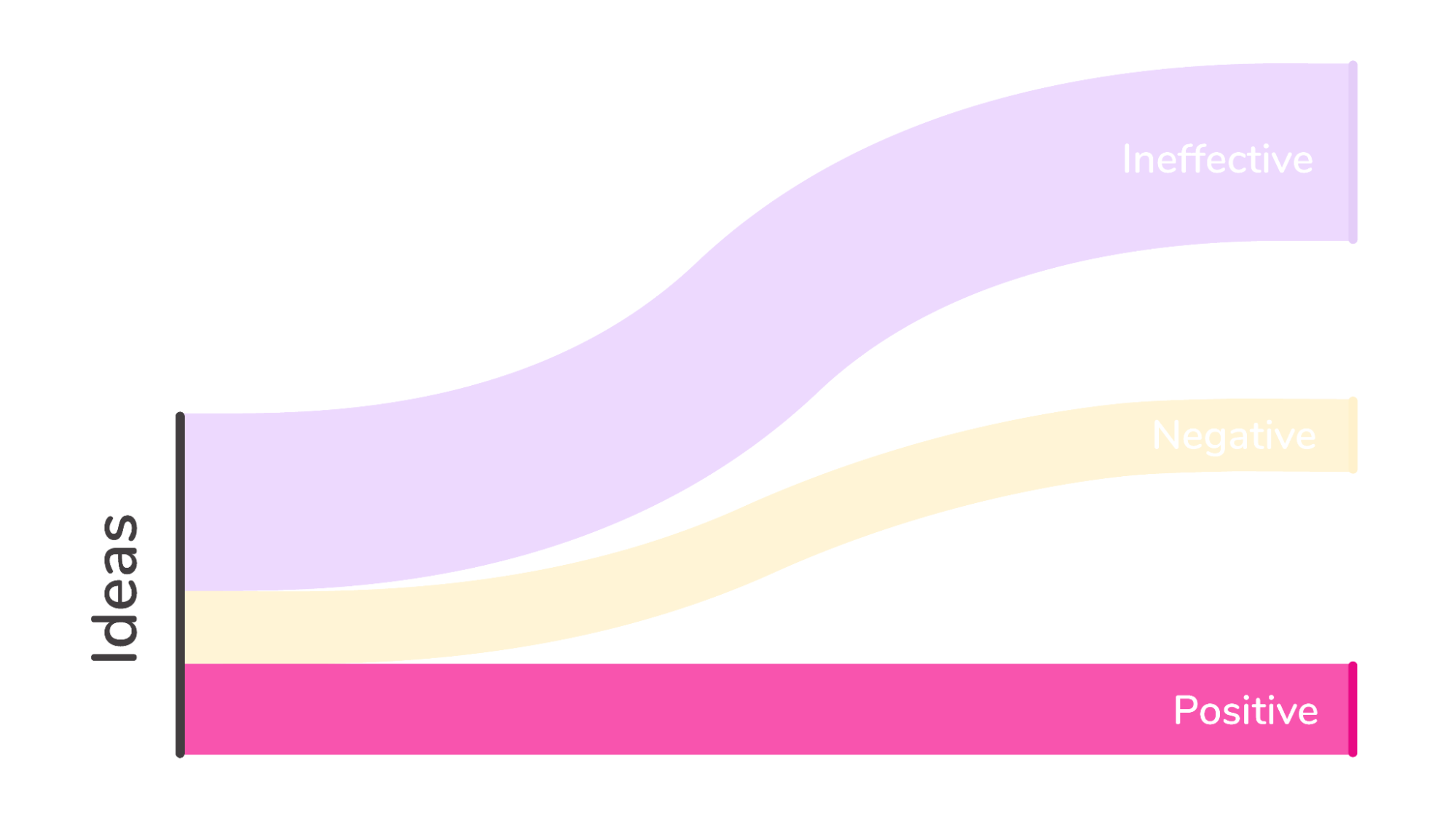

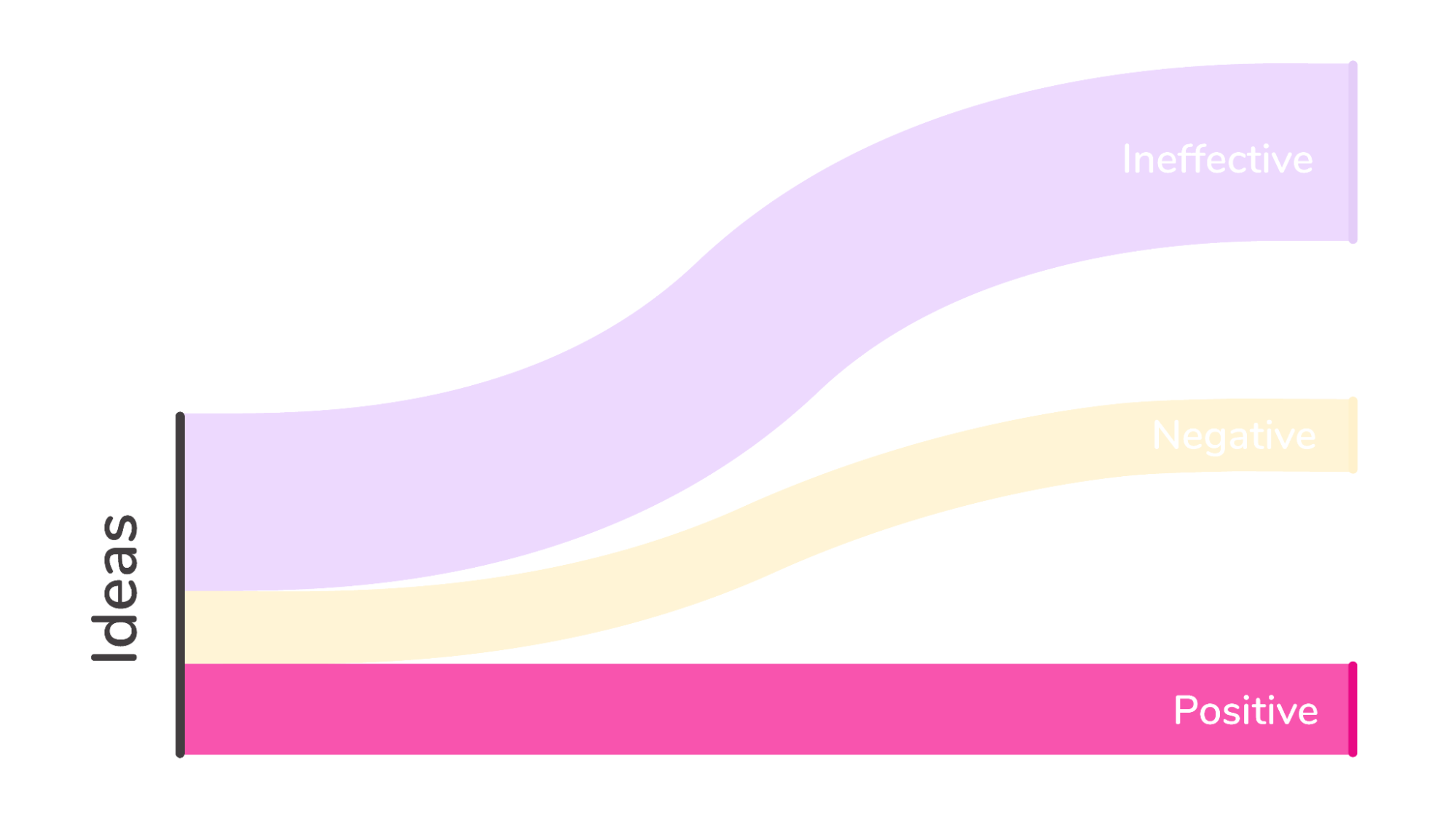

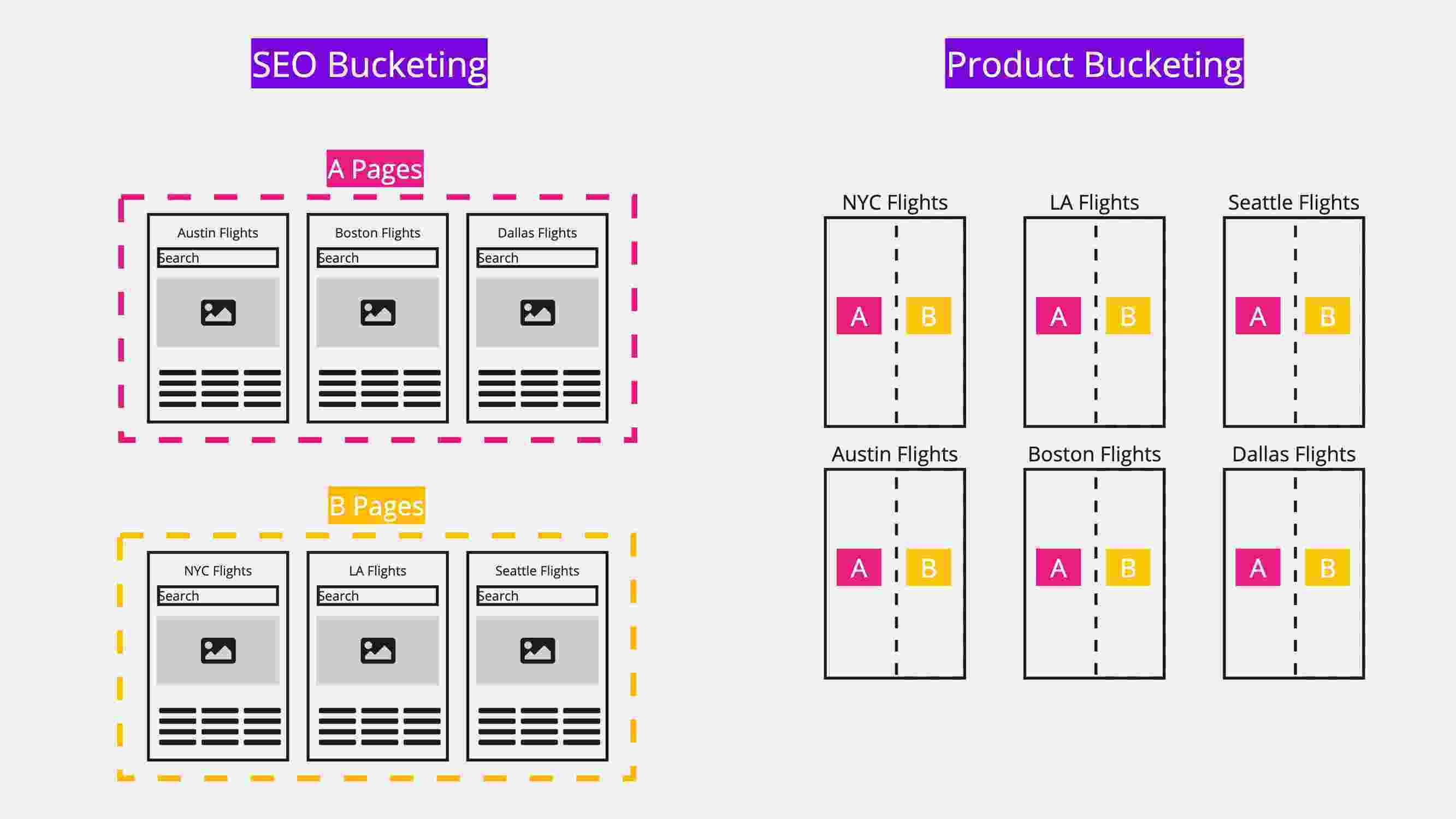

From our experience across huge numbers of tests on many sites and in many verticals, we know that the truth is that the real benefits of your on-site SEO program come from a relatively small fraction of the things you try. In our experience, the flow looks something like this:

(Net new content is a little different - if you want to read my thoughts on how new content and optimisation of existing pages should work together in a modern SEO program, check out my post on SEO moneyball.

It’s natural that big winning tests get all the glory and the breathless write-ups. Everyone wants to see graphs that go up and to the right. Some of the strongest business cases, though, come not from those wins, but from the lessons we learn from losing tests and the opportunities that come from tests that show no strong effect in either direction.

Of course we have written a lot about winning SEO tests and they have their place, but this post is really about the benefits of being able to identify all the non-winners, what we can learn from them, and what happens when we can do the filtering:

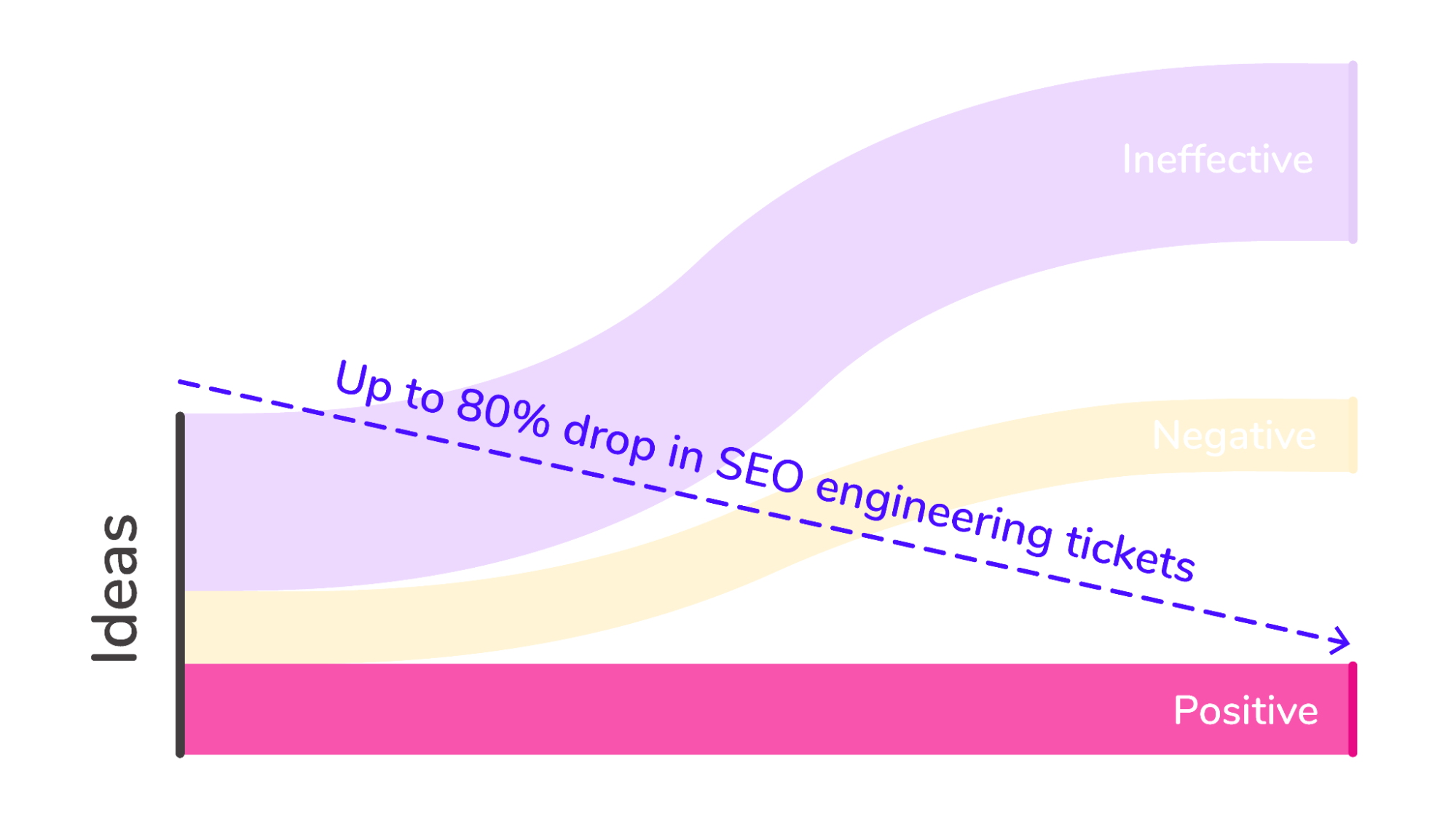

One of the big business cases for SEO testing is to be able to identify the negative and ineffective results with minimal engineering involvement. You can also improve the relationship between SEO and engineering if you can cut out all the non-winners before they reach the engineering backlog. This can enable you to capture all the positive benefits with as little as 20% of the engineering effort:

I’ve listed a few examples below of the kinds of changes that showed no result in either direction and those that turned out negative.

What kinds of changes show no result in either direction?

We might hope that everything we do would have an impact, but the truth is that an awful lot of SEO best practices, in the form of the common recommendations included in an agency audit, are based on ideas handed down through an untraceable history of blog posts, conference presentations, and training sessions. Some of them are of course real and valuable, but too many are no longer true, maybe never were true, or even if they contain a kernel of truth, aren’t true enough to justify the effort needed to roll them out and maintain them.

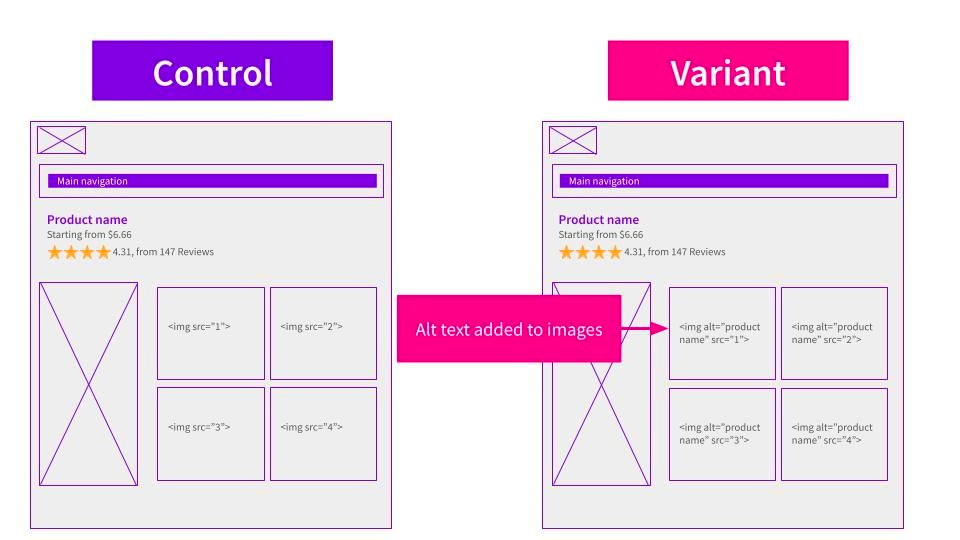

Example of historic best practice: alt attributes

There are very good accessibility reasons for adding descriptive information to images, but the pure organic search benefits have proved elusive in our testing.

There is no evidence that they are bad for organic search performance, but we have commonly seen SEO tests return no evidence that they are good for SEO either.

Too often, we have seen a test with a hypothesis something like “adding descriptive alt attributes to these images on the page will help search engines understand and value the page for searches for those attributes and result in more organic search traffic” turn out inconclusive (here is a detailed write-up of one such alt attribute test):

Example of a new hypothesis: E-A-T “signals”

E-A-T, or Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness is a shorthand for Google’s official line on the ways they are thinking about quality websites and high value content. The concepts appear in the quality rater guidelines, drive the philosophical direction of the iteration of the core ranking algorithm, and are used to guide the training of machine learning models to identify quality at scale (if you want to learn more about E-A-T, I highly recommend Lily Ray’s expert, authoritative and trustworthy guide!).

Naturally, when SEOs hear this, many start to ask themselves not only how to be more expert, authoritative and trustworthy, or even how to demonstrate how expert, authoritative and trustworthy they are, but how to seem more expert, authoritative and trustworthy. This is a natural outgrowth of the “ranking factor” way of thinking about organic search visibility, but it does tend to result in hypotheses that relatively surface-level tweaks to the presentation of existing content might be beneficial because they are nominally aligned with E-A-T.

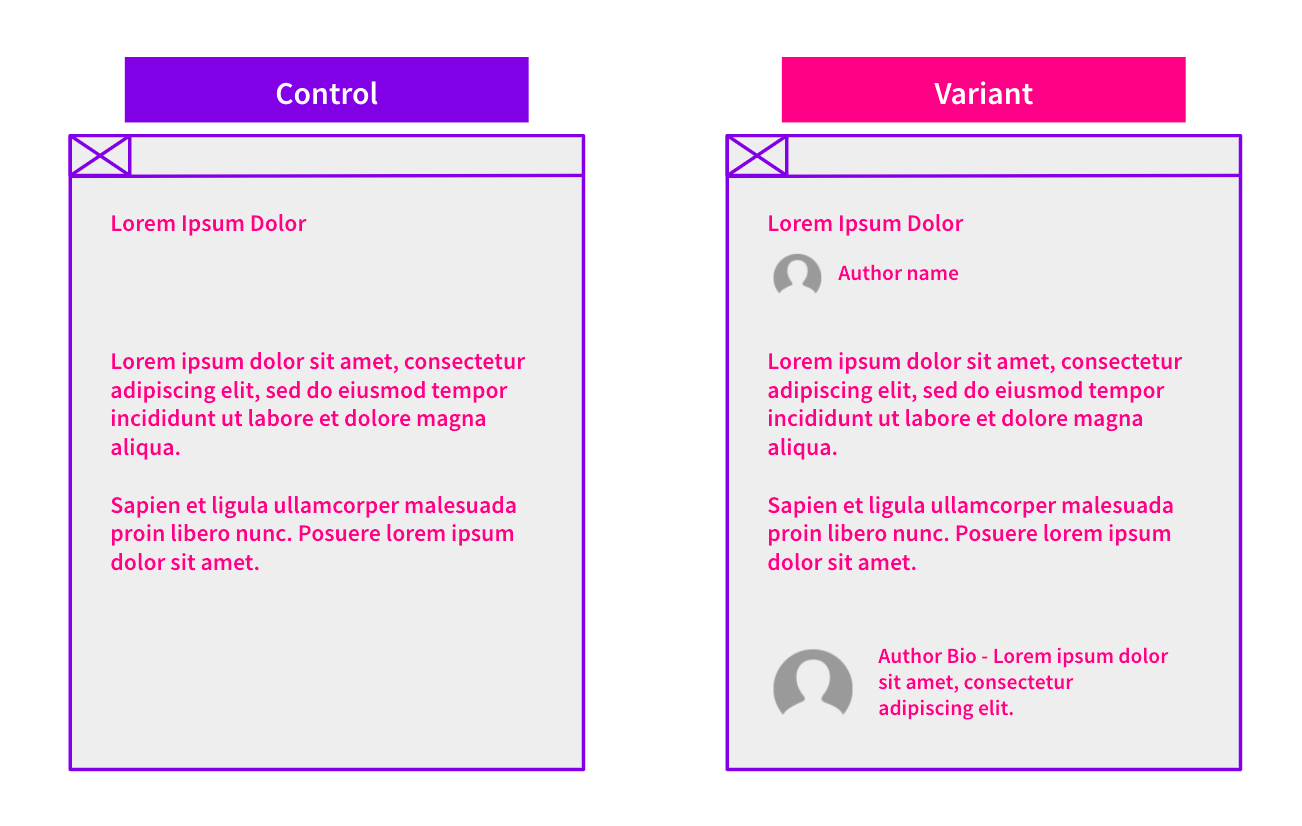

An example of this is adding lightweight authorship information to existing pages - a test that one of our customers found not to have strong impacts in either direction:

In reality, to improve Google’s view of the E-A-T of your website, you’re likely to need significant content overhauls if you have good reason to believe Google isn’t viewing you as authoritative. I delve into this more in my post: SEO moneyball.

What kind of changes turn out to be negative?

Simple binary best practices don’t tend to turn out negative - they are generally positive or just ineffective - but there are still common processes and best practice approaches that can generate sensible-seeming changes that turn out to be very bad ideas. And remember, ineffective SEO test results can contribute to wasted engineering time.

Probably the scariest of this class of sensible-seeming but actually very bad changes are cases where, through keyword research, we have identified a great-sounding opportunity that turned out bad. We have tons of cases, for example, of implementing changes to page titles based on keyword research and, for various reasons, seeing strong declines in organic traffic. It’s quite likely that this will become even harder to predict as Google continues to rewrite ever more titles and snippets for display in the search results.

As well as these “best practice process” examples, we also see “it depends” impacts where an identical-sounding hypothesis can have different impacts on different sites depending on details of how the site is set up, the industry it operates in, the competition it is up against, and the kinds of search it is competing for.

Example of a keyword-research-driven negative change

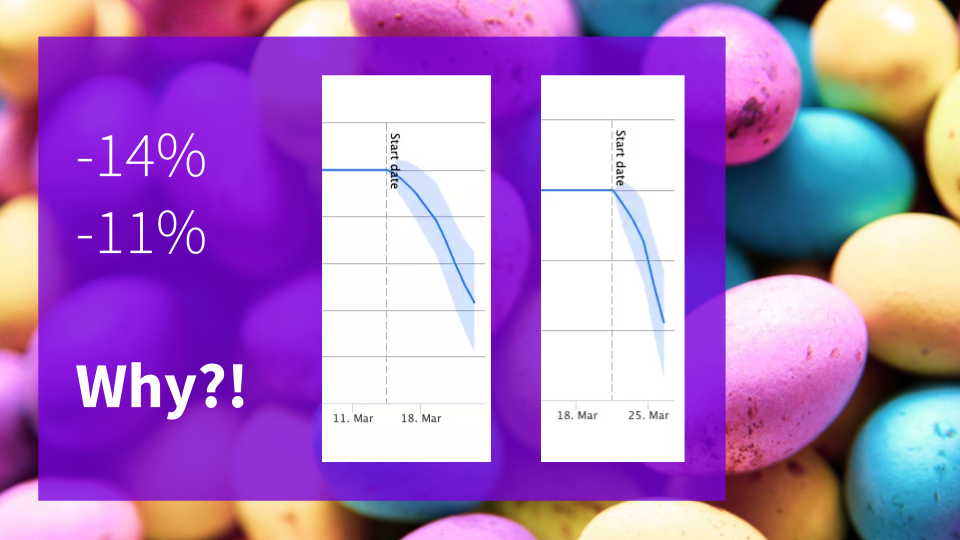

With the insight that many people modify their searches for flights and travel deals with seasonal modifiers such as “Easter”, one of our customers tested a hypothesis that the addition of this messaging in titles and meta information would be beneficial:

In fact, it turned out to be strongly negative in multiple different markets:

This was because the negative impact of the dilution to the core search terms (i.e. flights search for travel at any time) may have outweighed the possible uplift from the targeted seasonal variations. This test was also run on two different language markets. You can read the full details of the test here.

Example of a “it depends” negative change

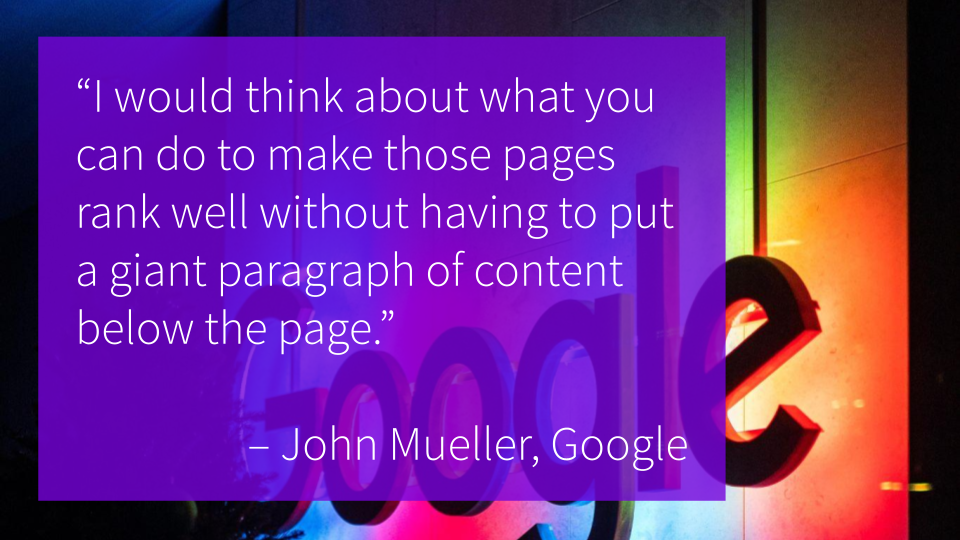

It is common in many verticals to have pages with relatively low quality (or even totally boilerplate) text at the bottom of them. For example, this is something that you see a lot on category pages on ecommerce sites. The official line from Google has long been to try to avoid this:

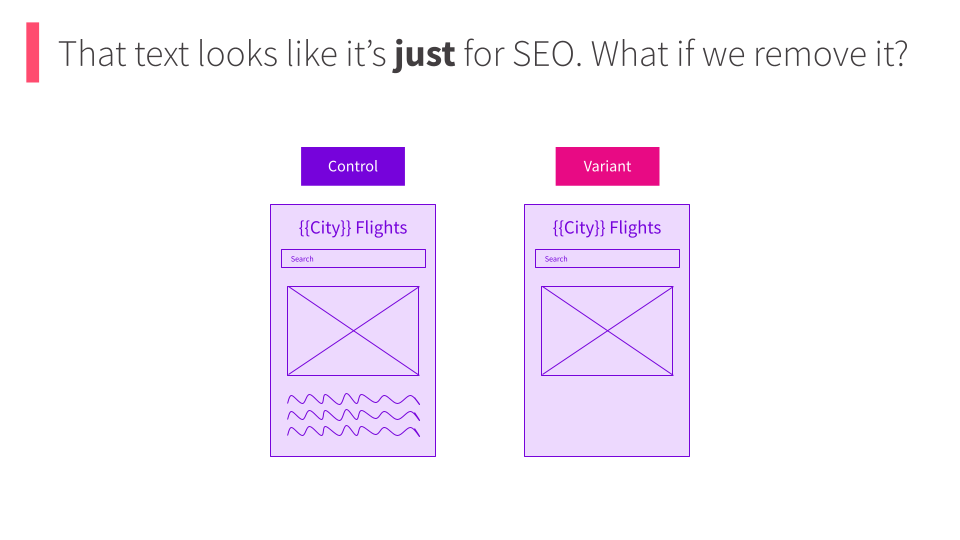

As a result, we see a lot of cases where smart teams look at text added to such pages years ago and ask themselves if it is still adding value. This can lead to a variety of hypotheses including running tests to determine the value of improving the copy, but it can also lead to hypotheses like “we’d be better off simply removing this bit of text we don’t expect real human visitors ever to read”:

While we have certainly seen this work in some situations, we have also seen strong negative outcomes from removing seemingly-poor text on some sites.

If you are interested in more examples, we have collated a list of 8 losing tests with a range of hypotheses and different kinds of negative outcomes. You can register here to be the first to get each new test result case study in your email when it’s published every two weeks:

Putting it all together: what we can learn from losing SEO tests

As SEO professionals, we can learn a lot about our craft from tests that don’t produce winning results. We can learn about historic best practices that either don’t work or don’t work well enough to be worth the effort. We can refine our recommendations arising from keyword research, and we can find out the answer to “it depends” questions for our specific site and situation.

As marketers in charge of entire SEO programs though, we can learn even more valuable lessons:

-

A smart SEO testing program can capture all the value of your existing on-site SEO activities for up to 80% less engineering effort.

-

It is hugely valuable to avoid the drag of marginal losses that comes from being unable to tell that changes have had a small (but compounding) negative impact.

These are the perhaps unexpected sources of return on investment that often drive the business case for increased SEO testing cadence, summed up in the visual showing all the ideas that we don’t need to implement with a strong SEO testing program in place:

If you want to learn more about the business cases for SEO testing, then you can read my colleague’s recent post about this and most especially on what leaders can learn from losing tests.

![[Webinar Replay] What digital retail marketers should DO about AI right now](https://www.searchpilot.com/hubfs/what-to-do-about-ai-thumbnail.png)