While having a controlled testing environment and sophisticated statistics and measurement are cornerstones to a robust experiment, so is the often-too-little-discussed hypothesis.

Forming a hypothesis has long been a crucial step of the scientific method and that doesn’t change when it comes to SEO testing, or any other form of user testing. However, the foundations of a strong hypothesis for SEO testing are unique.

We’ve created this guide to share with you how we go about formulating hypotheses at SearchPilot so you can begin writing your own.

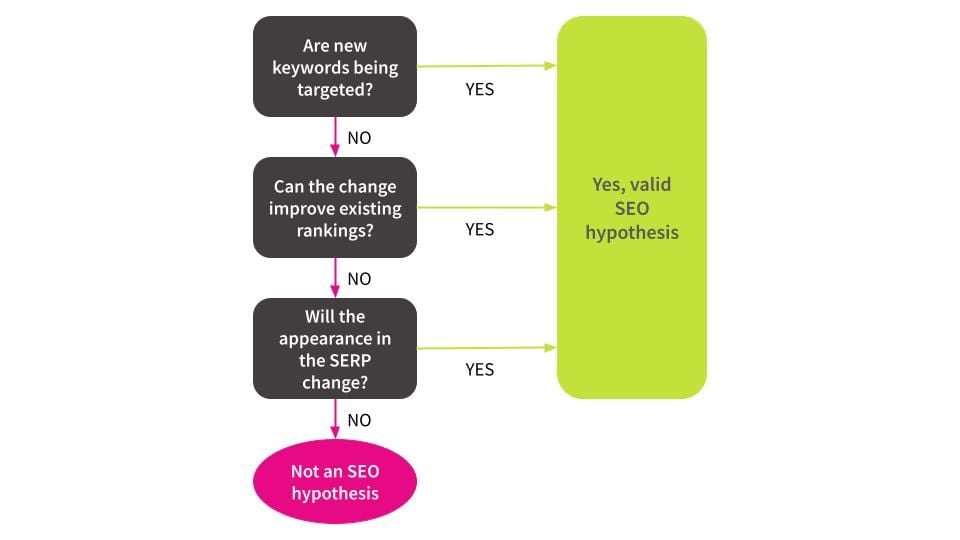

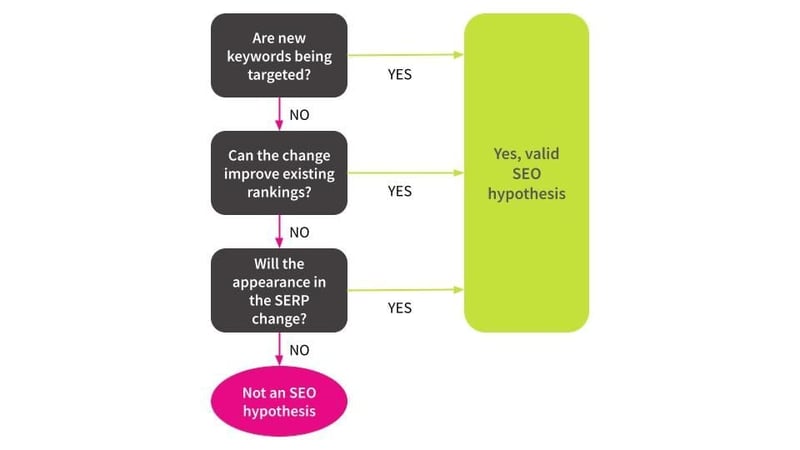

At the end of this blog post, we’ve also included a flow chart we use internally that you can use to quickly make sure that the hypothesis you are planning to test is a true SEO hypothesis.

Foundations of an SEO Hypothesis

You may not necessarily think of it this way, but when trying to improve organic traffic we’re talking about influencing some combination of three core levers:

- Improving existing rankings

- Ranking for more keywords

- Improving organic click-through-rates (CTRs) independent of improving rankings

While we as SEOs have a wide variety of different optimisations we can make to a website to improve its organic traffic, when we distill what we’re doing down to the basics every change that we make aims to impact one of these mechanisms or a combination of them.

As such, any SEO experiment you run - whether that’s through SearchPilot or any other method - should always be founded upon an SEO hypothesis that influences at least one of these three levers.

A test idea alone is not a hypothesis, and too often it’s treated as such. Without formulating a strong hypothesis prior to launching an experiment, when it comes time to draw conclusions from the test you can find yourself struggling to come up with explanations for why you’re seeing a certain result. A weak hypothesis leads to poor experiments and will prevent you from gaining valuable insights from your tests.

Mastering how to write a SEO hypotheses will help you quickly differentiate between strong and weak test ideas and help you prioritise the tests that are likely to have the biggest impact.

Introducing Conversion.com’s Hypothesis Framework

At SearchPilot, we follow a formula for writing our SEO hypotheses influenced by Stephen Pavlovich at Conversion.com.

In his blog post, Pavlovich identifies eight key components to a strong hypothesis:

-

Quantitative and qualitative data

- Quantitative data is anything that can be expressed as a number, or quantified - hence the name. Typically, this data will be associated with measurement units. For SEO tests, this can be something like organic sessions or organic click-through-rate

- Qualitative data is data that cannot be expressed as a number, and is instead data that can be observed and recorded. This type of data is collected through methods of observation, like surveys, interviews, and conducting focus groups. User studies would be considered qualitative data, for example.

-

Lever - for SEO testing these are the three mechanisms from our previous section: Improving existing rankings, Ranking for more keywords, Improving organic CTRs

-

Audience - the audience or segment that will be included in the test, for SEO tests this is “all visitors including googlebot” - which is important to avoid cloaking. We can do measurement segmentation though like, “mobile visitors only”

-

Goal - what is the goal for this test? For SEO testing, that will be which lever we’re trying to influence

-

Test concept - what are we changing to influence our chosen lever? For example, changing the meta description to impact organic CTRs

-

Area - the pages that you’re testing on and the part of the page you’re changing. This needs to be a subset of pages that gets sufficient organic traffic and a change that is likely to have a meaningful impact

-

Key Performance Indicator (KPI) - the KPI defines how we’ll measure the goal. For our purposes, that will be measuring organic traffic

-

Duration - this is how long you expect the test to run. It’s important to calculate this in advanced for CRO testing using a frequentist approach, but we take a different approach for SEO testing at SearchPilot that doesn’t necessitate us pre-determining the duration

These eight components are grouped into three sections of the hypothesis: “We know that”, “We believe that”, and “We’ll know by testing”.

This framework is useful for any type of testing in any industry, but because the scope of SEO is restricted to our three levers, we use a simplified version at SearchPilot.

We know that

This portion of our hypothesis must always focus on something we know already. That either comes from accepted industry truths about SEO, source material from Google themselves, knowledge we have about the domain that we’re testing on, or knowledge from previous tests we’ve run.

We believe that / possible effects

This section should focus on what we’re changing and which (one or more) of our three SEO levers we will be influencing.

At SearchPilot, we also commonly add a “Possible effects” portion to our hypotheses, where we think through the various reasons we might expect a positive or negative result. When it comes to interpreting your results later, this portion is valuable for drawing conclusions - especially when the results are surprising.

We’ll know by testing

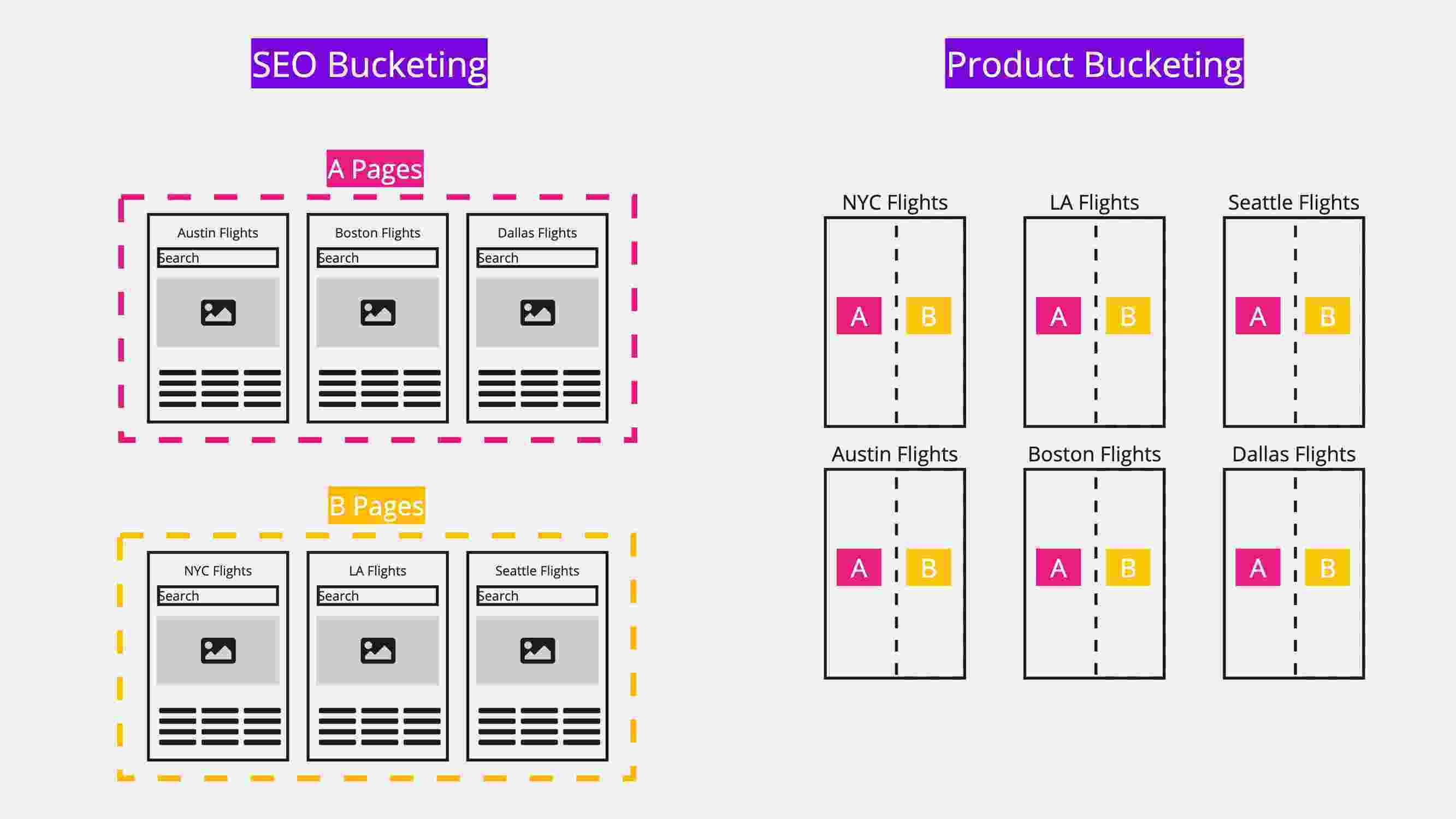

For us, this section typically remains the same and is founded on our testing methodology of splitting up pages and forecasting variant sessions. For tests with unique set ups, like internal linking tests, we will outline specific details on how we’ve set up the experiment.

Using The Levers to Apply This Framework to SEO Testing

By using the three levers - improving existing rankings, ranking for more keywords, or improving organic CTRs - you have the foundation of formulating strong SEO hypotheses. If your SEO hypothesis doesn’t clearly influence at least one of these three levers, then that’s a good indication it’s not a true SEO hypothesis.

More often than not, a change has the potential to influence more than one of these levers. Your SEO hypothesis needs to capture every lever the change you’re making has the potential to influence.

The overlap between the three levers means that data sources like organic rankings or CTRs can often contradict each other, making the results unclear and difficult to draw valuable insights from. That’s why we focus on organic sessions at SearchPilot - it reduces noise and ultimately, all three levers aim to influence this metric. You can learn more about our reasoning here.

Bearing in mind that we many SEO changes will appear in more than one of these sections, I’ll now focus on each individual lever in detail:

Improving existing rankings

When we talk about improving existing rankings, we mean ranking higher for keywords that our customer already ranks for rather than ranking for new keywords, which is its own lever.

Any SEO hypothesis that focuses on this lever should come back to basic ranking factors. These include but are not limited to:

- Adding existing key terms to title tags

- Updating headings or other on-page content to include existing key terms

- Getting more internal (or external) links - we tend to focus on internal links in SEO testing because external links are difficult to influence and test in a controlled way

- Improving page speed

- Improving Core Web Vitals (CWV)

- Similarly, changes that will improve user signals that Google may be measuring

Increasingly more we find that changes we make to customer’s websites have different results on desktop vs mobile, particularly for websites where the on-page experience differs a lot by device. These are differences like a user needing to scroll on mobile to see content that a user wouldn’t have to scroll to see on desktop, interstitial pop-ups that block content on one device and not the other, etc.

Additionally, mobile first indexing means that ranking factors will be primarily measured on mobile. When formulating our SEO hypothesis, we should bear how user experiences differ by device and how unique features of the mobile experience might influence organic traffic; we should also be sure to check our results split by device.

Ranking for more keywords

Again, there will be a lot of overlap here between levers. Many of the ways that you can improve your rankings for existing keywords are also ways to rank for more keywords. We call this improving the scope of keywords.

While improving your existing rankings improves organic traffic because higher rankings have higher CTRs (more on this in the following section), ranking for more keywords increases your organic reach, putting your website in front of more users and increasing your organic traffic as a result.

In SEO consulting, often consultants will spend a lot of energy trying to get clients not to forget about the long tail and stop focusing on high volume keywords. Although this lever is probably the rarest of the three that we try to impact and can only really be pulled by significant changes to our keyword targeting, we similarly shouldn’t forget that targeting more keywords with our SEO experiments can produce good results.

Experiments targeting this lever include but are not limited to:

- Adding new keyword targets to title tags

- Adding new keywords to headings or other exiting on-page content

- Adding new content blocks, like FAQ sections

- Getting internal (or external) links from relevant pages regarding topics that Google may not have previously associated with your pages

It’s good to keep in mind that changing your keyword targeting can have consequences for your organic rankings for your existing keyword rankings, and this should be captured in your hypothesis.

Improving organic CTRs

Increasing your organic rankings will inherently improve your organic CTRs and is what causes organic traffic to increase when you improve existing rankings. However, we can also improve organic traffic without improving organic rankings by just improving our organic CTRs, and these are common SEO experiments.

When we’re talking about an SEO test that is CTR focused, we’re specifically referring to changes that impact organic CTRs independent of rankings.

The best way to know if an SEO experiment is a CTR experiment or not is to consider if the change has the potential to alter the appearance of your website in the Search Engine Results Page (SERP). If the answer to that is no, then your experiment is likely to influence one (or both) of the rankings levers - or it’s not an SEO experiment at all.

Tests that target organic CTRs independent of rankings include but are not limited to:

- Changing title tags - most title tag changes can influence both rankings and CTRs. However, in some cases, such as adding prices, we are just trying to impact CTRs

- Adding structured data to get rich results

- Winning other rich results (like tables) from on-page content

- Updating meta descriptions

- More recently, since Google has started using other content for page titles, updating content that might be pulled into the title (only applies if this happens though)

- Adding data nosnippet attributes to influence what content Google uses in the SERP

Running Experiments With Weak SEO Hypotheses

Because of algorithm updates like page experience and the increasing influence user signals have on SEO, most changes we make to a website these days can arguably influence SEO. In general, we want to avoid running any experiments that don’t have a strong SEO hypothesis and that isn’t likely to have a substantial impact on organic traffic.

For tests that have weak SEO hypotheses, we should either avoid running them or if appropriate, consider running them as a full funnel or CRO-only experiments instead.

There are two main reasons to avoid running these SEO tests:

- SEO experiments have a long run time. At a minimum we run our experiments for two weeks - we rarely call an experiment before three weeks and for websites with less traffic it’s common for us to run experiments for six weeks or more. As such, running an experiment with a weak SEO hypothesis has a high opportunity cost.

- Recent research from Ron Berman and Christophe Van den Bulte indicates that a high fraction of all statistically significant results for commercial A/B tests are either false negatives or false positives. They call the percentage of statistically significant tests that are false negatives or positives the “false discovery rate”, or FDR. They found the FDR ranges between 18% and 25% for tests that use the standard 95% confidence interval for statistical significance, rather than the expected 5% rate. One of their key recommendations to reduce the risk of false positives or negatives was to focus on generating better ideas to test or run tests that are higher risk, but likely to have a higher impact. While this study was related to CRO tests, the lessons are relevant for SEO split tests as well. For our purposes, when we run experiments that have weak SEO hypotheses, we increase our risk of deploying changes that are not true positives or incorrectly avoiding changes that we believe will be negative, that in reality may have benefits to our website outside of SEO.

That being said, sometimes we still run experiments as SEO tests that have weak ties to our levers. These tests tend to only make sense when we are making sure there is not an unforeseen negative impact to organic traffic from a change we want to make for other reasons (like this experiment we ran). In these instances, we should always make sure that everyone involved understands that this experiment is unlikely to impact SEO, and clarify why we’re running it. Also, if we see a statistically significant result - especially a negative result - we will always need to consider the net overall impact in consideration of other key metrics like conversions to inform whether or not to implement the change.

Conclusion

Writing a good SEO hypothesis is crucial for any SEO tests we run, and an important skill to learn. Without a strong hypothesis, we run the risk of having conclusions we struggle to unpick and have a high chance of tests being false negative or positive.

If you take away nothing else from this post, when coming up with your SEO test ideas always remember your three levers: improving existing rankings, ranking for more keywords, or improving organic CTRs. If your change does not influence at least one of those three levers, it’s likely not a strong SEO test idea and might not be worthwhile to run.

SEO Hypothesis Flowchart

This flowchart is one we use internally and designed to help you quickly assess any hypotheses against the three SEO levers to make sure that they’re valid SEO hypotheses. If you can’t reasonably answer “YES” to at least one of the three criteria, then it’s likely you have a weak hypothesis and you should reconsider running the experiment, as discussed earlier.

Again, most SEO tests will impact more than one lever. Checking your hypothesis against each of the three criteria in the gray boxes will help you determine all of the levers you’re likely to be pulling.

![[Webinar Replay] What digital retail marketers should DO about AI right now](https://www.searchpilot.com/hubfs/what-to-do-about-ai-thumbnail.png)